- Home

- Robert Atwan

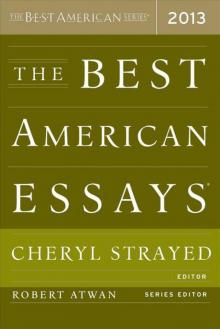

The Best American Essays 2013 Page 12

The Best American Essays 2013 Read online

Page 12

At the service, one of the last speakers said that Shoichi used to ask his women to make dishes for their church dinners. “Because,” she added, drawling, “of course he always had a woman.”

I winced. The audience laughed, but the remark seemed in poor taste, given that Toshiko-san was in the room—in the back row, where she had insisted on placing herself.

The service had been stocked with surprises, one or two even more startling than the fact that my father had continued the practice, initiated by Ellie, of attending church dinners. There was the letter, translated and read out loud by my older sister, from an old high school friend in Tokyo. Some of what the letter said I knew—tales of Shoichi’s effortless brilliance, for instance. But much of it was new. I hadn’t known that in high school he was popular with boys and girls alike, and friendly and generous to those less favored than himself. For as long as I could remember, he had been a poor conversationalist, an aggressive and mean-spirited debater, and a teller of boastful, embarrassing stories, the kind of person people avoided at parties and dreaded bumping into in the street. I hadn’t known that he always came in last in the 100-meter dash, and that his genial indifference to his lack of athleticism somehow added to his popularity and his aura of cool. I hadn’t even known that he still kept in touch with anyone from high school—sixty years ago!—let alone a man who would weep at his passing, write such a letter, and then round up every single graduate of their high school he could find so they could hold a memorial service of their own in Tokyo.

Another surprise was the picture that emerged of Shoichi as a young man. One after the next, his colleagues and former students told the same story: in the ’60s and ’70s, the lab was the premier center for fusion research in the world, overflowing with hope, idealism, and bright young men fired by the conviction that the discovery of a clean energy source lay within their grasp. And in that august company, Shoichi stood out. His brilliance—“that’s a word,” the first speaker from the lab said, “that I’m betting you’ll hear more than once today”—was legendary. If he was a little arrogant, prone to making mincemeat out of those with less ability—well, another speaker said with a shrug, with a mind like that, who could blame him?

They spoke of traveling across the country to study with him, quaking when they had to answer his questions, and angling for invitations to dinner at his house. They told of trusting that his genius would win the day for them, the lab, and mankind.

Shoichi had shared in their idealism. In the early ’60s, one speaker said, he had turned down a career in the barely nascent field of computers, even though he was certain that was the wave of the future. He’d been equally certain he could create a clean energy source and had deemed that the more critical step for humanity.

My father had been nine when atomic bombs decimated Hiroshima and Nagasaki; it made sense that he would grow up dreaming of harnessing nuclear power for peaceful and productive ends. But I hadn’t realized people once thought the lab might change the world. In the late ’80s, which is when I remember it best, it seemed quiet and a little sleepy, a place where smart men toiled dutifully over equations and tinkered with equipment. The optimism had leached out of them by then; they knew that if the lab did achieve its goal, it would not be in their lifetime. The problem was not that they had been wrong. They could, and did, create energy from fusion. But it took immense pressure and heat for the process to work, and the energy required to produce those conditions was always more than they could create. Theoretically they were on target, but for all practical intents and purposes they had failed.

Nor had I known that adoring students and colleagues once surrounded my father. The image clashed so violently with what I remembered that had my mother not said later that her memories of those times matched the speakers’ exactly, I would have assumed they’d made it all up. Shoichi lived just a few miles from the lab, but most of his colleagues hadn’t seen him for years. With each breakdown and hospitalization, their friendship with him had cooled, and when he retired, in 2000, it must have seemed easier to forget him. I can’t blame them. By then illness, medication, and electroshock treatments had done their damage. His mind was diminished and his body bloated. His hands shook, and his gaze was restless but no longer searching.

I wondered at first if the speakers were waxing nostalgic about Shoichi to compensate for their long neglect. But then I realized that they too had been disappointed by their careers. They weren’t famous; none of them had won the Nobel Prize. Their nostalgia was not for Shoichi so much as for those heady days at the lab when their ambition and their idealism had run side by side and success had seemed around the corner. Or if the nostalgia was for him, it was for the man he had been as well as for their own younger selves.

The fact that my father had “always had a woman” was not a surprise. He had liked the company of women, the more the merrier. Toshiko-san knew it, and probably many in the room did as well. He was boastful enough that it was difficult not to know this about him.

“Toshiko-san is the primary mourner here,” my older sister said in her opening remarks, “no question.” More than once I turned around to search for her, a trim, plainly dressed woman with an open face, fighting tears by herself in the back. But the room was too packed; I could not see past the fourth row.

Despite my sister’s words, at the reception afterward it was to us, the daughters, that the guests came to pay their respects, never mind that we hadn’t been involved in our father’s life in any serious way for years. Indeed, Toshiko-san probably received fewer expressions of sympathy than my mother, who had flown in from England to attend the service.

When they met, my father and Toshiko-san were both widowed and in their sixties. She had grown up dyeing kimonos with her family in Kyoto, hard work a fact of her childhood. During the Occupation she met an American soldier—an African American from Alabama and, as it later turned out, an alcoholic with a temper—who took her home with him. Together they had six children, one of whom she lost to pancreatic cancer. Not an easy life, yet somehow Toshiko-san emerged with her good humor intact.

She had moved in with Shoichi early on, but without ever giving up her own apartment, and for reasons that were never clear—his breakdowns, his moods, his untidiness, or his roving eye?—moved back into her own place after about a decade. He took her on trips to Japan, Europe, and Canada and cruises to beaches in sunnier climes; they ended their relationship more than once but always found their way back to each other. When I came to visit, they would take me to their favorite Japanese restaurant, where we’d share large boats of sushi. She would have too many beers and clamber to the front of the room to sing karaoke, mostly sappy songs, Christopher Cross and the like, her voice wavering in and out of tune, as my father watched and smiled, nodding his head ever so slightly to the beat.

She never called him by name. Instead she used the term sensei, an honorific title meaning “professor”—a sign of respect, maybe, or a joke, a way to gently mock him and bring him down to earth. I was grateful for it, since it made him laugh.

In the last two years of his life, he and Toshiko-san saw each other only once a week. They met every Friday for about an hour at a mall on Route 1 that stood almost exactly between their homes. Yet even if they saw little of each other, they talked. Toshiko-san told us after his death that he would call her twice a day, at nine in the morning and nine at night. She didn’t have to explain the reason for this ritual. The archetypal absent-minded scientist, Shoichi was indifferent to the progress of the clock. If he insisted on such precise times, it was because he was worried about his body lying there, undiscovered, for hours or even days.

As it was, the funeral home director said that based on the decomposition of his body, a full day must have passed before he was discovered. Shoichi had not phoned at night, but since that had happened before, Toshiko-san decided to wait for the morning call. When that didn’t come, she had flown into a panic and sped the eight miles to his house.

She banged on the door and then ran around tapping on all the windows. She had the key but was too frightened to use it. She went to the neighbors, a nuclear physicist and his wife. They had lived next door since I was a baby and were used to helping out; the last time my father was found raving in the backyard, clad in nothing but boxer shorts on a brisk February day, it was they who called me. With them, Toshiko-san went into the house to find Shoichi dead on his bed, the television blasting.

Five days later, my sisters and I assembled with Toshiko-san at the funeral home for a viewing of the body. Shoichi had requested a cremation; the viewing was just for the four of us.

He was dressed in a gray suit. His face looked sunken. The room was cold and dimly lit.

It was a while before I realized that Toshiko-san was talking. “Look like he’s sleeping, neh.” She was rocking back and forth, her eyes streaming. “Wake up, sensei. Wake up. Itsumo nebo. Look at him, so handsome in his suit.” She turned to us, and we—huddled silently together in a corner, my younger sister red-eyed—gaped back. “You see how handsome he is?” she said. Then she turned back to the body. “What’ll I do without you, neh, sensei? Who’s gonna take me on nice cruises?” Reaching into the coffin, she gave him a push on the shoulder, hard enough to leave an indentation. “Wake up, wake up.”

When she and Shoichi met at the mall on Route 1, they would stroll, look into store windows, and chat. Sometimes they would have lunch or a snack, but this was never the primary purpose of the visit. She would reminisce about events from her past as well as theirs, catch him up on her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, and scold him for scrounging at flea markets and accumulating yet more clutter. He would ask a question or toss in a remark here or there; at times he threw his head back and laughed, something he did rarely in the last few years of his life, and then only with her. He’d have little news to impart of his only grandchild, whom he had met just two or three times; in his last decade he and my older sister were seldom in touch. But I like to think that at least once during those weekly walks he broke his customary silence to speculate about his granddaughter and that Toshiko-san wondered with him. Did she still play with stuffed animals? Had she mastered fractions yet? How tall had she grown?

An Asian man and an Asian woman, stooped and gray-haired, their conversation slipping from Japanese to English and then back again: anyone seeing them would have taken them for a long-married couple, out shopping for a toy for a great-grandson.

Toshiko-san had loved my father. But my younger sister was right—his feelings for her were open to question. He had been resolute in his refusal to marry her. Whenever I’d ask him about it, he reminded me that she was seven years older than he was. He didn’t want to bury another wife. Ellie’s death, from complications resulting from diabetes, had been too hard. He couldn’t go through that again.

I’d point out that Toshiko-san was in great health and that women usually outlived men. And besides, isn’t it better to live for the moment? Was there something else he wasn’t telling me?

It made no difference what I said. He wouldn’t change his mind, nor would he explain further.

So perhaps he hadn’t loved her. Was it possible, though, that he hadn’t loved any of his women?

At the end of the memorial service one of his MIT friends had come up to me. He said that in the weeks leading up to his death, Shoichi had remarked that manic depression had ruined his life. I hadn’t been able to collect myself enough to respond, and the man ran off before I could find out his name, so I couldn’t call him later to ask what aspects of his life my father had meant. I assumed at the time that he had been referring to his career. Only later, and only because of the train of thought that the talk with my sisters had started, did I wonder if he could have been talking about his personal life too.

That my father had not fulfilled the academic promise of his early years—that he, unlike the nuclear physicist next door, had not been summoned to Sweden to dance with the queen and receive the Nobel Prize—was old news. I had made my peace with that disappointment long ago, even if he never could. But the idea that love had also eluded him was new, and harder for me to accept.

He had sacrificed his homeland, his health, and his family for his career. If it had gone as well as he’d hoped, I wouldn’t mind as much that his love life had not. Then too, I knew from my own experience what balm relationships could provide. Struggling with my third novel, I had taken refuge in the company of my husband as well as my mother, sisters, and friends. Had my father not had recourse to this solace?

If only I could believe that his failure to love, like his inability to work with consistency, get out of bed every morning, and keep his temper in check, was a matter of faulty brain chemistry. But I couldn’t. Over the years I’d grilled my father’s psychiatrists, internists, and nurses and read clinical texts, scientific papers, and memoirs about manic depression. I knew about the controversies surrounding its diagnosis. I knew the difficulty of understanding how exactly it affects the brain, and the many problems associated with lithium, the most reliable medication currently available. I knew that alcoholism is a symptom, that travel can trigger a manic episode, that studies link the illness with creativity, and that it runs in families. I knew that it could make people say and do things they didn’t mean and hurt themselves as well as anyone else in the vicinity. I knew how Van Gogh walked into one of the wheat fields he had been painting and shot himself in the chest; how Woolf weighted her pockets with stones and waded into the Ouse; how Hemingway pushed the barrel of his favorite shotgun into his mouth and blew out his brains; how Plath stuffed wet towels into the cracks of the doors in her kitchen and her children’s bedroom before turning on the oven and sticking her head into it; how both Rothko and Diane Arbus took barbiturates and sliced their veins with razors; how Anne Sexton put on her mother’s old fur coat, closed the garage door, and started her car; how Kurt Cobain fled rehab, hid out in Seattle for days, and then went to his garage to shoot himself in the chin; how Spalding Gray jumped off the Staten Island Ferry into the East River; how David Foster Wallace hanged himself on his patio, and how the designer Alexander McQueen, taking no chances, overdosed on cocaine and tranquilizers, slashed his wrists, and then hanged himself in his wardrobe with his favorite brown belt.

But nowhere had I heard that manic-depressives can’t love. On the contrary, Andrew Solomon writes that even though deep depression might temporarily impair one’s capacity to give and receive love, “in good spirits, some love themselves and some love others and some love work and some love God.”

If my father had not loved any of his wives or girlfriends, it was a decision he had made. He had opted for isolation. Unexpectedly, when I considered this possibility, what I felt was not grief or even pity but fear.

So I wrote to Ellie’s younger daughter. We had gone to high school together, and though I hadn’t seen her for years, we had reconnected at the memorial service. I asked if she thought that my father had loved her mother. I begged her not to sugarcoat. What I wanted, I told her, was the truth.

Yes, she wrote back, I think he did love her. With men, it’s sometimes hard to separate love from pride, and I think he was very proud to have her as a wife. They had fought a lot, especially over money, but they had enjoyed their church community and loved their trips to Japan. He was not a simple man and, consequently, a simple happiness was not in his nature, she concluded, but I did know him to have moments of simple pleasure and obvious joy.

She was trying to reassure me, that was clear. But there was truth in what she said. Shoichi had been proud of Ellie. He had always admired large, fleshy women—a hangover, I’d always thought, from the near starvation he had suffered as a boy in wartime Japan—and Ellie had been huge, her flesh straining against seams and spilling out of shirt openings. I’d forgotten that they had argued about money as well as God, but perhaps the good times had outweighed the bad; perhaps pride did equal love.

Yet I

didn’t believe it.

I called my younger sister in San Jose. Five years younger than I am, she was just nine when our parents separated—too young, she says, to remember much about our father’s whiskey-fueled rages. They hadn’t been close, but her relationship with him had been less complicated than mine was, and as a teenager she had spent a lot of time with him and Ellie.

“You said you thought he loved Ellie more than anyone else,” I said. “Why?”

For a moment she was quiet. Then she laughed. “Process of elimination.” She was seven months pregnant, glowing and huge, and her laugh sounded happy. She does not look much like our father—none of us do—but she has his grin, sudden and bright. “Think about it. Who else is there?”

“Oh,” I said. “Oh. I thought that maybe you knew something about them. Maybe from when you went on vacation with them, at the beach.”

“I remember—” She stopped.

I pictured her eyes growing distant, as they do when she wants to guard her thoughts.

It took some prodding, but eventually she told me about a fight she’d overheard them having, just a few months after their wedding. From what she could gather, Ellie had been trying to get him to pay a credit-card bill. He had told her that since she, as his wife, was now on his health plan, all of her diabetes-related expenses covered, she had no right to expect anything more. “It went on,” my sister said, “but that was the gist of it. So I’d say that the marriage probably sucked—though maybe less than his other relationships.”

“Maybe things changed,” I said, knowing even as I spoke that they hadn’t. “They had ten more years together after that. That’s a lot of time.”

The Best American Essays 2013

The Best American Essays 2013