- Home

- Robert Atwan

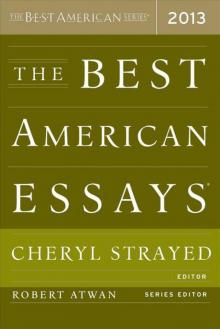

The Best American Essays 2013 Page 13

The Best American Essays 2013 Read online

Page 13

“Maybe. But it was a bad fight.” She paused. “Listening to it, I thought about what you’d told me about the fights he and Mom used to have, and I was glad I didn’t remember much about them.”

It was with scant hope that I turned to the only candidate left. My mother is an artist and writer, hard at work now on her eighth book, an account based on interviews she has conducted with Japanese veterans of World War II. In this and everything else she has the unflagging support of my stepfather, a smart, well-read business executive whom she has been married to for over twenty years. In England for New Year’s, I went to see her in her study. I told her I wanted to hear about her relationship with Shoichi, and she nodded as if she had been expecting the question. The story unfurled slowly.

“I could see he was special,” she said, “the day he showed up on our doorstep.” He had come to call on her parents at their summer home near the mountains of Karuizawa. He was seventeen, she a year younger. He was stamp-collecting in the area, and since his mother was a distant relative of her father’s, he had decided on impulse to pay them a visit—so what if they had no idea who he was? He had shaggy hair, a balloon of a head, and the easy sophistication of a Tokyo boy. He had been confident, personable, outgoing—“Yes, that really was your father back then,” my mother said, nodding, though I had not stirred—and her parents were much taken with him. He spoke only with them, as if he were an adult, but she eavesdropped on their conversation and heard enough to be impressed.

In the fall he traveled from Tokyo to Nagoya to have dinner at their home. By winter he was a regular guest. My mother, already in love, sought out his company whenever she could. They struck up a correspondence, their relationship progressed, and she thought their future together was assured.

But he held back. Maybe, my mother said, because of a girl he still liked from high school. Then one day he wrote to say he would marry her only if she promised always to obey him. Unnerved, she stopped writing for a while, but he continued to send letters, one containing a proposal without qualifiers. She began writing again, although she held off on a response, and she was there at the airport when he left for Boston in 1958. Another year would pass before she finally said yes.

“So I boarded a plane from Tokyo to Boston,” she said, “a daikon stashed in my purse.”

I nodded. The story of how she had flown halfway around the world carrying almost nothing but the daikon, the white Japanese radish my father had been longing for, was lore in our family, the sweetness of her gesture unsullied and perhaps even heightened by the years of acrimony, abuse, and infidelity that followed.

“We had a few good years in Cambridge and when we first moved to Princeton,” she said. “It was when we lived in Japan for those two years that he began to lose his mind.” She said that Shoichi woke her up one night and told her to alert the authorities. He needed five hundred soldiers to come and surround the house: the enemy was coming and they were prepared for attack. He was an alien, a prince who had fled from another world in a small computer. But the alien enemy had found him at last, and hiding was no longer an option.

Shoichi became angry when she refused to call the police. All night he kept talking about the enemy; every time my mother fell asleep he would jerk her awake. He stayed at home in this state for three days, until finally she had to call the authorities.

This was in the early ’70s; I was seven. I didn’t think I remembered any of it when my mother first began speaking, but as she continued there was a flicker, a memory of my father standing on a table, backlit by the Tokyo sunset, and yelling as my sisters and I scurried around on the ground and cried.

When she went to visit him in the hospital after he was committed, he greeted her with a look of polite confusion. Then his face cleared. “Oh, I know you,” he said. “You have three daughters, don’t you.”

To reassure herself more than him, she reached out to touch his hands. They were so cold that for a moment she wondered if he was in fact an alien.

They would stay together for seven more years. He would take to wandering outside the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, saying that he had important secrets to impart to the emperor. She would fly out to Italy to rescue him when, instead of delivering a paper on the levitated superconductor multipole experiment, he ranted to hundreds of stunned physicists from all over the world that he needed to see the pope because he was Christ reborn. He would end up in the hospital again and again, and at his family’s insistence my mother would explain to colleagues and friends that he was there for a heart condition, a lie that would become the truth more than three decades later. We would return to Princeton because she, missing America, put her foot down, something my father never forgave her for, and they would fight and have affairs. At PPL colleagues and former students would shun him and dismiss his ideas, citing his megalomania and illness, and he would drink too much, grow increasingly violent, and become a regular at the local mental institution, and one rainy day in April, when he was away on one of his long trips to Japan, we would pack up and move away, leaving just a note behind.

But it was when he failed to recognize her for the first time that my mother realized that in order to survive, she would have to pull away from him.

“It was hard at first, and then—” Her voice, when she continued, was low. “Then it wasn’t.”

I knew she had been struggling since the memorial service, wondering whether she should have stayed, and if she could have saved him.

“You were right to pull away,” I said. “If you hadn’t left him, you wouldn’t be around now, and who knows where we’d be. You know that, don’t you?”

She brushed aside a phantom wisp of hair and looked down at her hands. In her mid-seventies she is still beautiful, the delicacy of her features undiminished by age. “I know.”

I took a deep breath. “Just one last question,” I said. “Do you think—” Somewhere along the way my eyes had filled. I slashed at them with an arm. “Did he ever love you?”

She glanced at me before looking away again. Then she said the phrase that I thought of as the refrain of my childhood. “He was really sick.”

I nodded. “But that didn’t mean he couldn’t—”

“And he loved physics so much,” she said. “There wasn’t a lot of space left after that.” Her eyes met mine. “So no. No, I don’t think he ever did.”

She spoke without bitterness. It was a long time ago, and she knew as well as I did that if my father had not loved her back, it was his tragedy rather than hers.

I was lugging my suitcase down the stairs on the last day of my visit when my mother called to me from the second floor. I looked up. Her face was flushed, and she was waving a small black book. Back in Princeton, she said, Toshiko-san had given her Shoichi’s address book so she could call family members who needed to be informed of his death. She’d been going through it and had just discovered a current address for Masako-san, the girl he’d liked in high school. “You know, the one that made him reluctant to marry me.”

She had seen her once, she said, at the airport on the day Shoichi departed for Boston. A host of his friends had gathered to see him off. Masako-san had been the only other girl in the crowd, and my mother had known at once who she was.

She was small, smaller even than herself, my mother said, and lovely and poised. She had a Mona Lisa smile, and she had smiled a lot at my father that day, though she had cried too.

She had lupus. Shoichi’s parents had forbidden him to marry her because they feared that his children would inherit the condition. Other Japanese parents would have felt the same, which was why my mother knew that Masako-san could never have married.

She waved the address book again. “Don’t you see, he kept in touch with her,” she said. “He never forgot her.”

I was still, imagining my father bent over a girl even smaller than my mother, a crowd of his friends pressing in on him as the time for his departure drew near. I thought of him writing to her, going to see her

when he was in Tokyo, and missing her when he was away.

“Maybe he loved her all his life,” my mother said.

She looked hopeful, even though what she was saying was that the relationship that had consumed twenty-four years of her life had been a sham from the start, and I knew that somehow she had sensed what was behind all my questions.

“Maybe he always missed her,” she said. “Maybe all the other women in his life somehow fell short.”

I smiled. For a moment I’d been swept up by the story. But a high school crush that had lasted all his life—it was the stuff of movies. What she’d handed me was a Rosebud moment, and I was too earthbound to believe that my father could be explained by it. “I don’t know about that,” I said.

“You sure?” she asked, but the hopeful look was already fading. “Well, maybe you’re right. It’s hard to know anything about anyone, isn’t it?”

“Especially him,” I said.

She laughed. “That’s true.”

Looking up at her, I had a sudden urge to tell her everything. That I was guilt-stricken about never having returned my father’s last phone call to me, three weeks before his death. How shocked I’d felt when my father’s MIT friend said that Shoichi had believed manic depression ruined his life: perhaps I was naive or optimistic or in denial, but I hadn’t realized that he considered—that he knew—his life had been ruined. I wanted to confess to her how small I’d felt at the funeral home, when my own grief had proved a pale, flimsy thing next to Toshiko-san’s, and what I had just understood, that behind my research into my father’s relationships lay my own guilt and fear. Because if my father had never loved the wives and girlfriends who had loved him and nursed him and stayed by his side, what hope was there for me, the daughter who had fled his home and returned as seldom as she could? If I relayed these thoughts to my mother, perhaps she could untangle them and smooth them back into something less terrible.

Yet nothing she could say would explain my father. Whether because of his devotion to physics, his illness, or a deficiency deep inside him, he had never loved any of us, at least not in any way that mattered. Besides, she had suffered enough because of him; there was no reason to add to the guilt she felt for all the ways his life shadowed my sisters’ and mine. Far better to tell her the one definite conclusion I had reached after my two-month inquiry into my father’s life and loves: that he linked me to her, and for that I would always be grateful.

But the airport taxi was crunching gravel outside; with a sigh she was beginning to make her way down the stairs toward me. For now we were out of time.

So I squinted up at her instead. “Masako-san, huh?”

She shrugged. “It’s nice to think so, isn’t it?”

And I told her that it was, and I wished with all my heart that I could.

WALTER KIRN

Confessions of an Ex-Mormon

FROM The New Republic

I DON’T REMEMBER the missionaries’ names, only that one was blond and one was dark, one was from Oregon and one was from Utah. They arrived at our house on secondhand bicycles, carrying bundles of inspirational literature. They smelled, I remember, of witch hazel and toothpaste. The blond one, whose hair had a complicated wave in it and whose body was shaped like a hay bale, broad and square, wiped his feet with vigor on our doormat and complimented my mother on our house, a one-story, ranch-style affair in central Phoenix that never fully cooled off during the night and had scorpions and black widow spiders in the walls. The boys—because that’s how they looked to me that evening, when I was thirteen and my brother was eleven and my parents were in their mid-thirties—shook hands with us and sat down in the living room, where my mother had set out lemonade and cookies and my father had turned off the television so we could talk. They smiled at us. They smiled with their whole faces. Then they asked, softly, politely, if we could pray.

It was 1976, the Bicentennial, and not a good time for my family. We were sinking, mired in gloom, isolation, and uncertainty. We’d moved to Phoenix a few months earlier, driving a U-Haul truck from Minnesota that wouldn’t go faster than 50 miles per hour and didn’t have room for all of our furniture. We’d left the small river town where I’d grown up because my father, a corporate patent lawyer who loved to hunt and fish in his spare time, had soured on the Midwest. He felt bored there, constrained by dull conformity; a vision of fierce desert freedom had come over him. In Arizona, a land of opportunity, booming and unfenced, he planned to enter private practice and spend his weekends outdoors under the sky. He’d fly-fish in the mountains, he’d shoot quail, he’d buy a Chevy Blazer with four-wheel drive, and he’d take us deep into the red-rock canyons to hike and camp and hunt for rocks and fossils. We’d love it, he told us. Our fresh American start.

But it didn’t turn out like that. My father cracked. Too much longing and space, too little guidance.

It began when his own father died of lung cancer after a horrifying, swift decline. When my father returned from the funeral in Ohio, his legal practice was failing for lack of clients. Some mornings he didn’t bother to go to work, just sat on the bench at his bus stop and browsed the paper, waving on the bus drivers when they pulled over. He started talking to himself in public, while eating in restaurants or buying shotgun shells. The tone of his ramblings was punitive, exasperated, like that of an angry coach. Addressing himself as Walt, in the third person, he charged himself with foolishness and weakness. “Walt, you pathetic idiot,” he’d say. “Walt, you ridiculous stupid little ass.” Sometimes strangers heard him and turned to stare.

The story of how the Mormons came was this: Headed home from a job-hunting trip to Blackfoot, Idaho, while changing planes in Salt Lake City, my father suffered a breakdown in the terminal. His haunted mind attacked itself, nearly paralyzing him at the gate. He pulled himself together and boarded his flight, where he found himself seated beside a handsome young couple who radiated serenity and calm. They sensed his despair and started talking to him about their church, the center of their lives, and about their belief that the family is eternal, a permanently bonded sacred unit. (One reason he listened to them, he later told me, is that there had just been a terrible flood in Idaho—the deadly Teton Dam disaster—and he’d heard stories of how thousands of Mormons had immediately dropped what they were doing and convoyed in from states across the West to perform acts of cleanup and reclamation.) The next morning, in his bed at home, he woke up thrashing from a nightmare. My mother threatened to leave him; she’d had enough. Flashing back to the couple on the plane, he opened the phone book, found a number, dialed it, and said he needed help. This minute. Now.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints must have been used to fielding such distress calls. They dispatched a rescue party instantly: another couple, retired, in their seventies. Within an hour they were at my father’s side. They talked to him all morning behind closed doors and convinced him to go to church with them that Sunday. The service soothed him, lightening his mood. My mother saw this, grew hopeful, and didn’t leave him. The bicycle-riding missionaries showed up a few nights later.

“Dear Heavenly Father,” their prayers began. They sat hip to hip on our sagging old blue sofa, and milky beads of talcum-powder sweat ran down their temples and their cheeks. They blessed our family, our home. They blessed the lemonade. They asked that we hear their message with open minds. On the first night, they showed us a movie about a boy, Joseph Smith, who, one day in 1820, prayed in the woods behind his parents’ farm and found himself face to face with God and Jesus. The lessons that followed described what happened next, from Smith’s translation of a golden scripture that he found buried in a hillside to the trials of his early disciples. Seeking peace to practice their new faith, they traveled west from settlement to settlement, harassed by mobs of brutal vigilantes, who finally murdered Smith in Illinois. His people stayed strong, though. Under a brave new leader, Brigham Young, they undertook a 1,000-mile trek that brought them to Utah, their Zion in

the wilderness.

The missionaries kept coming for six weeks, always at night, always hungry for our cookies. On Sundays they sat next to us at services, one on each side of us, like gateposts. And then it was time; they told us we were ready. Standing in a pool of waist-deep water, dressed in white robes, we held our hands together as if to pray, let the missionaries clasp our wrists, leaned back, leaned back farther, and joined the Mormon Church.

Last winter I sat drinking coffee in my living room, watching Mitt Romney speak on television after narrowly winning the Michigan primary. The speech was standard Republican stuff, all about shrinking the federal government and restoring American greatness, but I wasn’t concentrating on Romney’s rhetoric. I was examining his face, his manner, and trying—if such a thing is possible—to peer into his soul. I was trying to see the Mormon in him.

My motives were personal, not political. I’d never been a good Mormon, as you’ll soon learn (indeed, I’m not a Mormon at all these days), but the talk of religion spurred by Romney’s run had aroused in me feelings of surprising intensity. Attacks on Mormonism by liberal wits and their unlikely partners in ridicule, conservative evangelical Christians, instantly filled me with resentment, particularly when they made mention of “magic underwear” and other supposedly spooky, cultish aspects of Mormon doctrine and theology. On the other hand, legitimate reminders of the church hierarchy’s decisive support for Proposition 8, the California gay marriage ban, disgusted me. Deeper, trickier emotions surfaced whenever I came across the media’s favorite visual emblem of the faith: a young male missionary in a shirt and tie with a black plastic name badge pinned to his vest pocket. The image suggested that Mormons were squares and robots, a naive, brainwashed army of the out-of-touch. That hurt a bit. It also tugged me back to a sad, frightened moment in my youth when these figures of fun were all my family had.

The Best American Essays 2013

The Best American Essays 2013