- Home

- Robert Atwan

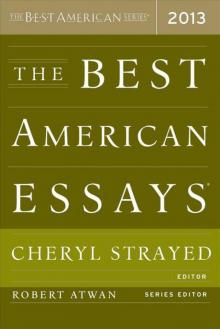

The Best American Essays 2013 Page 14

The Best American Essays 2013 Read online

Page 14

As for Romney himself, the man, the person, I empathized with him and his predicament. He no more stood for Mormonism than I did, but he was often presumed to stand for it by journalists who knew little about his faith, let alone the culture surrounding it, other than that some Americans distrusted it and certain others despised it outright. When a writer for the New York Times, Charles Blow, urged Romney to “stick that in your magic underwear!” I half hoped that Romney would lose his banker’s cool and tell the bigoted anti-Mormon twits to stick something else somewhere else, until it hurt. I further hoped he’d sit his critics down and thoughtfully explain that Mormonism is more than a ceremonial endeavor; it constitutes our country’s longest experiment with communitarian idealism, promoting an ethic of frontier-era burden-sharing that has been lost in contemporary America, with increasingly dire social consequences. Instead, Romney showed restraint, which disappointed me. I no longer practiced Mormonism, true, but it was still a part of me, apparently, and a bigger part than I’d appreciated.

Sometimes a person doesn’t know what he’s made of until strangers try to tear it down.

A few months after our baptism in Phoenix, having recovered the basic power to function, my family moved back to rural Minnesota, to a town about 40 miles from St. Paul where Mormons were few, and we promptly began to lapse. My little brother got all caught up in sports, my father resumed drinking wine and beer with meals, and my mother immersed herself in a new job as a nurse at a famous addiction clinic devoted to the gospel of the twelve steps. I remained faithful, however. I hung on. To abandon my family’s deliverers so quickly seemed risky to me, not to mention impolite. What’s more, I’d become a believer.

The teaching dearest to my young heart related to the transit of the soul through time and space and beyond them. The version of heaven familiar from my childhood, instilled in me by occasional attendance at a Lutheran Sunday school, had always struck me as sterile and impersonal—a cavernous amphitheater of clouds where rank upon rank of stranger-angels sang the praises of a seated wizard—but the Mormon afterlife seemed homier, a sort of family reunion among the stars. Like Dorothy waking from her dream of Oz, I would find myself resurrected with my close relatives, all of us smiling and at the peak of health.

One evening at church, a participatory play was staged to help us envision this reassuring place. Following a simulated plane crash that involved cutting the lights throughout the building and broadcasting sounds of chaos on the PA system, the congregation was ushered down a dark hallway into a room where the bishop and his wife stood dressed in white garments, illuminated by spotlights. Their arms were extended in welcome. Soft music played. Behind them were posters of galaxies and planets and a banner that read, THE CELESTIAL KINGDOM.

Another source of uplift was my new status as a deacon of the Aaronic Priesthood, a junior spiritual order open to all faithful adolescent males. Chief among my duties as a deacon was the ritual shredding of loaves of Wonder Bread into little sacramental chunks. Every Sunday my teenage pals and I would file down the aisles of our modest chapel distributing this holy meal, which also included paper cups of water filled from a tap concealed behind the pulpit. In my powder-blue suit and shiny brown clip-on tie, I felt handsome, useful, and respected. I also felt included, a new sensation for a kid worn-out from changing schools. As I moved through the congregation with my tray, the grateful faces in the pews, male and female, young and old, dissolved my chronic feeling of separation and convinced me I’d found my place.

The strongest force binding me to the church, however, wasn’t religious but hormonal. I found the girls of my ward more attractive than the girls at school. Perhaps because Mormon custom encourages young folks to marry permanently and early, often when they’re barely out of their teens, the girls were precociously skilled at self-enhancement, favoring leg-slimming, grown-up-looking shoes and eye-catching, curling-iron-assisted hairstyles. They also permitted discreet erotic contact that stopped just short of actual intercourse. The girl I liked best of all was Carla H., a hell-raising cheerleader two years my senior. Carla had sinful menthol-cigarette breath and a scandalous reputation. A couple of months before I fell for her at one of the ward’s monthly Saturday night dances, she’d run away from home, the story went, and shacked up with the married manager of the franchise restaurant where she worked. The better-brought-up boys avoided her because of this, but I, a new convert, was undeterred.

Carla’s family, whom I’ll call the Harmons, was Mormon royalty. It traced its ancestry to pioneers whom Brigham Young had dispatched to southern Idaho to irrigate the desert and start farms. The pious stoicism of these tough people was still discernible in Mr. Harmon, a midlevel corporate accountant with a lean gray face and hollow eyes who rarely spoke directly to his children, just mentioned them in mealtime prayers. Above the desk in his orderly home office hung a rack of rifles and shotguns, and after dinner he’d pull a chair up under them and organize the ward’s books for hours on end while Carla and I watched television in the next room and Ken, her nineteen-year-old brother, smoked marijuana and tinkered with his Camaro in the garage. I felt bad for the man. He seemed defeated. One evening he emerged early from his office and caught me and Carla with our shirts half off, but instead of saying anything, he walked silently past us into the kitchen, where I heard him turn the faucet on and splash water on his face. A few moments later he went by again, still ignoring us, holding a glass of milk.

My problem was that Carla wasn’t loyal. I was her Mormon boyfriend, not her main one. Her main one was older than me and twice as tall. I glimpsed him once, at the counter in her restaurant, dressed in a letter jacket covered in pins. I knew from his posture somehow that he and she had gone places I hadn’t. My consolation was knowing that in theory, she and I had a serious future together. In only three years I’d serve my mission, sent by the church to wherever they’d choose to send me—England, I hoped, because I was bad at languages but pined for foreign lands—and when I got home, I’d be urged to take a wife. It might be her. She’d hinted as much one night. “I’m getting this out of my system,” she confided while we lounged in her brother’s Camaro smoking dope. “Don’t think this is permanent. I love the church. I just can’t give all of me right now.”

I too had begun having trouble giving all of me. To my parents, the backsliders who no longer knew me, I was a scripture-reading wonder boy whom the elders sometimes invited to speak at services on topics such as “Teamwork” and “Moral Purity,” but I knew better. I’d turned into a sneak. At my most recent bishop’s interview—a ritual grilling required of every Mormon above a certain age—I’d been asked a series of questions that opened, absurdly it seemed to me, with this one: “Have you committed murder?” No, of course not. “Theft?” No again, though it depended. “Have you masturbated?” I started lying then. I lied right on down the remainder of the list. What’s more, I was pretty certain that we all did. So why put us through the whole confusing ordeal? To be asked if you lied and be forced to lie again was annoying and dispiriting. It prevented you from pretending you were good, which is sometimes, with kids, what helps you to be good.

The summer I turned sixteen, I joined my youth group for a ward-sponsored bus tour of the midwestern Mormon holy sites. The site I most looked forward to visiting was the spot in Independence, Missouri, where I was told that God would establish his everlasting kingdom around the time of the Second Coming. The way I’d heard it from a clued-in buddy who’d grown up in the faith, we would be called, via skywriting or trumpet blast, to gather at this consecrated place and erect a temple with our bare hands. We would go there on foot, the way the early saints had crossed the plains to settle Salt Lake City. It sounded like fun to me, and my buddy said it would occur within our lifetimes, after a period of shattering destruction. We didn’t need to fear this havoc, he said, because of the stores of food and other supplies that the church encouraged us to stockpile. I didn’t let on that my family hadn’t done this.

/> We left St. Paul and followed the Mississippi down along the continent’s great valley of primitive fertility and mystery. In the buses, especially as evening fell, a cloistered sense of boy-girl possibility caused sweaty hands to wander in the rear seats, beyond the view of the chaperones up front. In the morning we strolled through Nauvoo, Illinois, the city where Smith and his followers sought refuge after being chased out of Missouri. Our attention was directed to a hill where Smith had begun the construction of a temple, the rites and ordinances of which, my buddy whispered, were based on ceremonies Smith had witnessed in a Masonic lodge that he belonged to. “He stole them?” I asked. “So they say,” my buddy said. “They say it was Masons who killed him, for taking their secrets.”

Below the hill, on the flats along the river, was a cluster of wooden stores and houses restored by the church as a living history lesson. Standing some distance from Carla to fool the chaperones, I watched with pretended fascination as reenactors dressed in coarse, dull fabrics rendered fat to make soap and spun thread on wooden wheels. The impression I gained was that we—spoiled modern teenagers—were in some manner heirs to these simple, cheerful drudges. When the going got tough after the Day of Judgment, we would shed our luxurious individuality, take up their tools and their rough-hewn way of life, and set out on the overland march to Independence. I could almost imagine this transformation in my case—my parents’ house was surrounded by dairy farms, I’d been working at an auto shop that summer—but I doubted that Carla would make the grade.

On down the river we drove, into Missouri. The buses pulled over in a parking lot overlooking a leafy summer cornfield bordered by a tangled hardwood forest. We filed out and were made to stand in silence before what one chaperone, balding, tall, and stern, declared to be Eden, man’s childhood home. It was also the spot where Jesus would return to rally the elect, he said. We were shown the broad rock where, according to our guide, the Savior would stand and speak. We were encouraged to stand on it ourselves. The boy who preceded me in line was crying when he stepped down off the stone, one hand pressed on his stomach as though it ached. As Mormons, we’d learned that a burning in our bellies meant we were in the presence of the Spirit, whose job was to confirm for people in doubt the truth of propositions their minds resisted. This was one of those. Eden in a cornfield? It had to be planted in something, I supposed, but then there was the matter of its size. For Adam and Eve it was spacious enough, perhaps, but could it hold all the Mormons who’d be left after the tribulations of the Last Days? Only if they packed in awfully tight.

As Carla and the others watched me, I mounted the rock in my untied tennis shoes and awaited intestinal confirmation of a story I suddenly found preposterous. Other tales from the trip had strained belief, but I’d strained back and managed to accept them. This one was different, though. This one hurt to think about.

What happened next surprised me. As I gazed at the field and struggled to imagine a sea of faithful saints gathered to take instruction from God’s son as nuclear mushroom clouds billowed on the horizon and vultures circled above the woods, my stomach cramped. Not a strong cramp, but a cramp. Was this the same as a “burning”? Well, say it was. What prompted it, though? I feared I knew: pure tension. The tension of glancing over at my friends and wondering if I could conceal the look of emptiness that comes from finally losing one’s spiritual innocence.

Paranoia overtook me afterward. When I boarded the bus and headed toward the back row where Carla and I had sat on the way down, enmeshed in our comfy, conspiratorial romance, I saw that she wasn’t there, that she’d changed seats. She’d plunked herself down across from a male chaperone, in a zone of good conduct where nothing could happen between us. She seemed to avoid my eyes when I approached, then turned around to face my chatty buddy in the seat behind her. I walked on past her and sat by myself with a radio I’d brought. It may have been all in my head, the change in Carla, but the change in me felt real. Later on, when we reached Independence, I played sick and listened to the Bee Gees on the bus while my friends continued with the tour.

Beverly Hills, California, 2008.

I’m forty-six, which is all grown up and then some, and I’m scanning a list of online classifieds for an affordable guesthouse or apartment where I can stay while pursuing a new relationship with a woman I met over the Internet and drove all the way from Montana two weeks earlier to meet for a first date. I have other business in the area—shooting is about to start on a movie of one of my novels, Up in the Air, and the director and I have things to talk about—but I can easily finish up tomorrow, at which point I’ll face a choice: stay on in my costly, claustrophobic hotel room, secure a monthly rental, or say goodbye to Amanda (for now? for good?) and head back north toward Montana up I-15.

I narrow my list to three places, all guesthouses, and hastily arrange to meet their landlords. My lousy credit scores will be a problem. My life has been spiraling down these past few years. A divorce from the mother of my two kids. Fat medical bills from repeated bouts of kidney stones, which are one of those puzzling ailments you blame yourself for because the doctors can’t tell you what else to blame. A dwindling income due to a contraction of both my stamina and the publishing industry. I’m using Ambien to sleep, Ritalin to yank me back awake, and three varieties of narcotic pain pills to keep me from going fetal on the sidewalk when the stones start axing through my ureter. I should talk to my father, who has been where I am now and took extreme measures. But those measures aren’t open to me—I closed them off—which may be one reason I’m in this mess.

I never served my Mormon mission. Decision time came when I was seventeen, the year I left Mormonism altogether and began my college education rather than postponing it to proselytize. The disenchantments of the bus tour had savaged my testimony but spared my spirit, allowing me to rebuild my faith around elemental principles of love and forgiveness, charity and sharing. What finally separated me from the church was a loss of nerve, not a crisis of belief. My time in the ward had shown me at close range that God doesn’t work in mysterious ways at all, but by enlisting assistants on the ground. I saw sick people healed through the laying on of hands, not suddenly and magically but gradually, from the comfort that comes of feeling the group’s concern. I’d heard inspired messages spoken in common English, sometimes from my own excited lips. This proximity to the sacred scared me off. Too much responsibility, it felt like. Too much pressure to side with the miraculous, which places demands on a busy, modern person. You sit down on a plane beside a gloomy lawyer who’s cursing himself under his breath, and instead of ignoring him and reading a book, you have to ask his name and offer solace.

My stated excuse for sneaking away from Mormonism was skepticism about its doctrines, but I’d learned that most Mormons don’t grasp all the teachings of Joseph Smith—nor do they credit all the ones they do grasp. After the bus trip to Eden, holy Missouri never came up again in conversation. As for the future temple in Independence, I found out that the spot where Smith said it would rise belonged to a Mormon splinter sect with a U.S. membership of about one thousand. The “sacred underwear”? It was underwear. Everyone wears it, so why not make it sacred? Why not make everything sacred? It is, in some ways. And most sacred of all are people, not wondrous stories, whose job is to help people feel their sacredness. Sometimes the stories don’t work, or they stop working. Forget about them; find others. Revise. Refocus. A church is the people in it, and their errors. The errors they make while striving to get things right.

But I didn’t have the patience, or the humility. I wasn’t a son of stubborn pioneers. I was the son of the lawyer on the plane who’d suffered the breakdown I thought I could avoid. I left the church as abruptly as I’d entered it. No formalities, no apologies, no goodbyes.

When I meet with the first two landlords in Beverly Hills, they’ve already seen my credit files and don’t seem to want to know much more about me other than why I’m standing on their property. At my third stop, I s

peak into an intercom and wait in suspense for an electronic gate either to slide open, meaning yes, or fail to budge, meaning time to hunker down, kick the opiates, and pay my bills.

“Great to meet you, Walt. I’m Bobby Keller. You want a Sprite or something? You look all hot. My sister, Kim, who you talked to on the phone, is at a church thing with our other housemates, but I can show you the place we hope you’ll rent.”

You can scoff at their oddities, skip out of your mission, run off to college, and wander for thirty years through barrooms and bedrooms and courtrooms and all-night pharmacies, but they never quite forget you, I learned that day. How had Bobby discovered my secret? My Wikipedia page, written by some stranger. It was loaded with mistakes (it said I was still married, a detail that may have given Bobby pause when Amanda stayed over the next night—not that he said a single word), but the fact that got me a lease without a credit check and rescued my new romance was accurate: my first book, a collection of short stories that opened with a tale of masturbation and ended with one about a drunken missionary, had won a little-known literary prize from a broad-minded Mormon cultural group.

I furnished the guesthouse with chairs and shelves and tables that my new housemates had stored in the garage and not only gave me but helped me clean and move. My latter-day Mormon double life began. Away from the shady, walled-in canyon compound that I nicknamed Beverly Zion, I plunged into the arcade of bright temptations that my single and in-their-twenties new friends (Bobby, a personal trainer turned surfing photographer; Kim, a runway model turned mortgage broker; Sophie, a TV talent show contestant; and Lisa, a sales rep for a cosmetics firm—identities that I have tweaked for the sake of privacy) had presumably banded together to resist. I patio-postured at the Chateau Marmont. I Sunset-Stripped until the bands went home. What I didn’t do was go back to church. Unnecessary. Mormonism, the religion of second chances, the faith that makes house calls, had come back to me.

The Best American Essays 2013

The Best American Essays 2013